We had a chat with Elliot Vredenburg from the brand-defining creative studio Public Address to talk a bit about how he got into graphic design, their recent branding project with The Foresight Studio, and about his ways and means to get inspiration.

Behind Brands™: An interview with Elliot Vredenburg from Public Address

How did you get into the world of brand identity design — and what made you stay?

I had a somewhat circuitous route to, from, and back to graphic design, but like many others, I started as a teenager with a pirated copy of Photoshop. That combined with mid-2000s skateboarding, streetwear, graffiti, and music made me learn how to replicate what I was drawn to — namely rap mixtapes, Mass Appeal magazine, and Stüssy t-shirts. Much later, after testing the waters of academia, art, and nonprofits, what finally made me come back to design was ultimately restlessness — working for three months at a time in completely different industries on completely different projects is what makes graphic design interesting.

Is there a perfect brand identity brief? What does it look like?

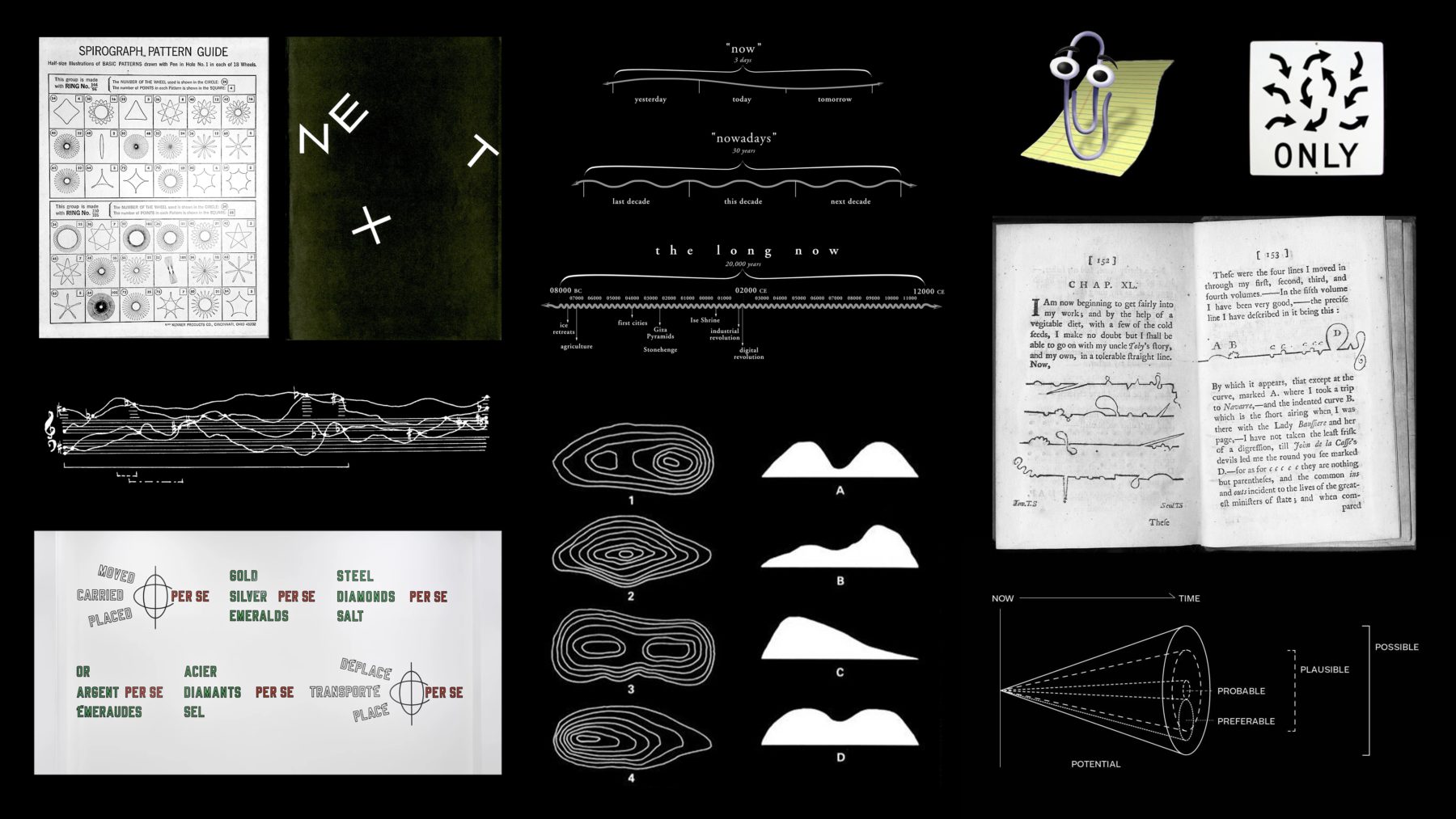

There is — in fact, we’ve already received it. Our friends at The Foresight Studio provided us with this, at the beginning of our work together. If I may:

1. We like Uncertainty

2. We like Heraldry

3. We like Systems of Systems

4. We like the Cartography of Time

5. We like Notations of all Kinds

The smaller the brief, the bigger the ideas. You hear a lot of rationalizing of limitations and constraints as a way to improve design, but more often than not, overly prescriptive briefs mean resorting to an established design language; employing tropes and clichés as familiar signifiers. In a world where everything looks the same, ambiguity allows for the unexpected.

You just recently created the visual identity for The Foresight Studio. How do you creatively approach a project like that — from beginning to end? Can you walk us through the creative process of designing this?

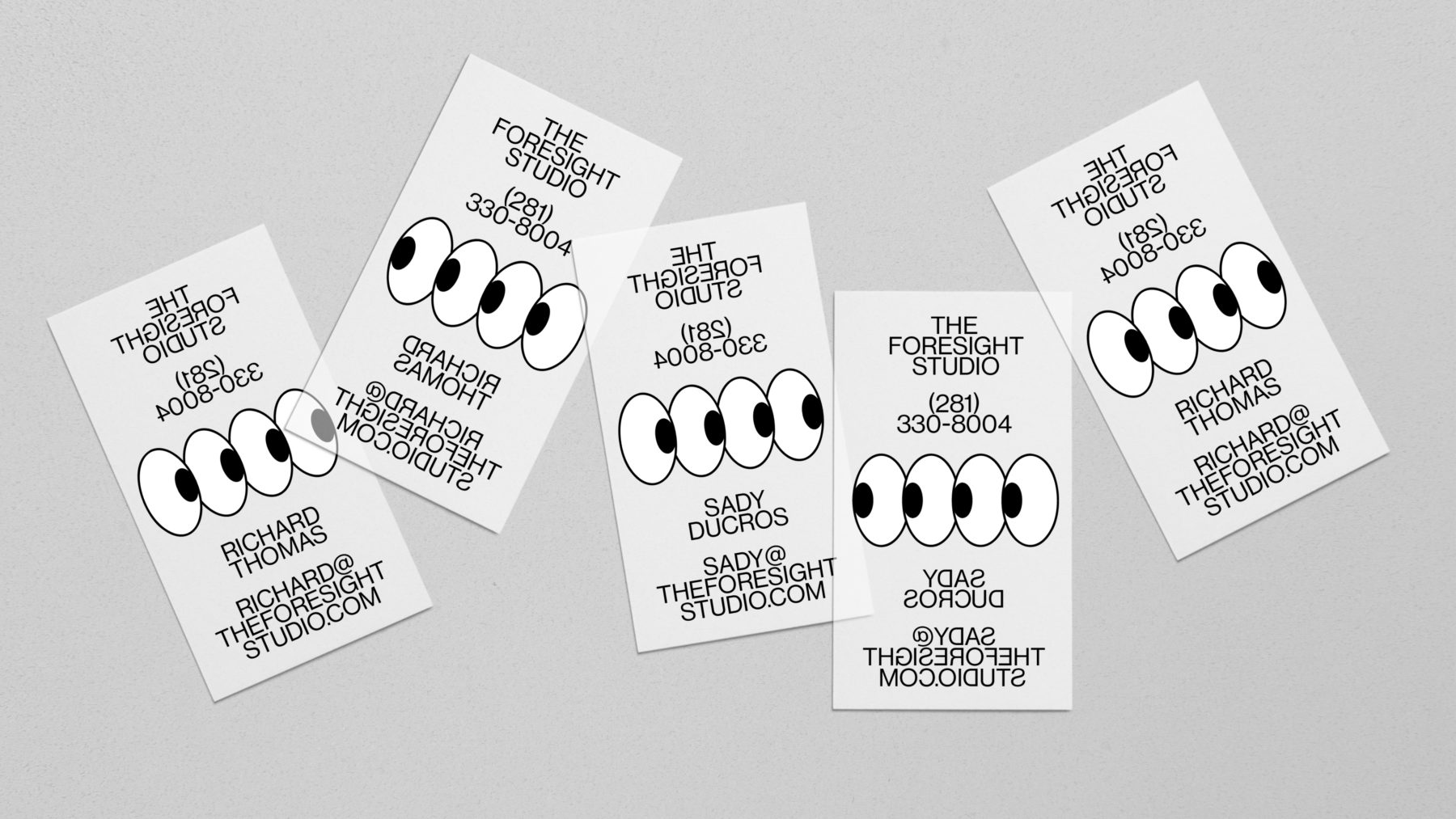

After receiving the brief, we had a few informal conversations with The Foresight Studio team about their genesis story, what they do, and their hopes and dreams. They’re not your typical client — they’re both professional and informal, they’re addressing pressing issues without being depressing, and that their work is fluid and purposely undefined. They present business strategy in the context of an art gallery. These contradictions made the brand hard to sum up in any kind of systematic way.

This kind of opacity was one of the most interesting characteristics of the brand. Representing that wasn’t something we could convey through a single concept, so we opted for breadth over depth — instead of two or three concepts with numerous mockups, we ended up with ten, with just a few shared applications, and anything specific that helped illustrate their core idea. These spanned the gamut from graphic representations of history, to differential framing of events and images, to simple visual puns. In other words, quantity and quality.

After sharing these with the team at The Foresight Studio and discussing their merits at length, we landed on a few we liked that were equal parts weird, practical, stupid, and smart. Mashing up different concepts created some interesting tensions to experiment with. We tested them on the most hardworking and the most pointless use cases we could come up with. They definitely didn’t ask for silicone phone cases or an Instagram Story Filter, but that doesn’t mean they won’t need them!

How was the team put together — and how many people are usually involved in a project?

Thankfully we have a team with a pretty diverse skill set, so we’re never trying to fit square pegs into round holes. On this project, there were four of us on the design side: myself, our creative director Chris Braden, and designers Andi Bordt and Annie Milova (Andi made the stickers; Annie posted two emoji that later became the brand). We’re always exploring ways to combine and recombine our team, and we often have a (first-string) player or two on the bench in case we need some extra help pushing a project past the finish line.

What is your preferred client/studio relationship or process when working on a brand identity?

We actually try not to have any clients. We aim for partners instead. We’d much rather work with someone rather than for them, for a few reasons. The best work comes from trust. By subverting the conventional client relationship, we can build confidence in each other’s opinions and skill sets. I’ve worked in studios where I’ve never even met the clients and only received feedback in a game of broken telephone. Without those barriers, we avoid turning these relationships into adversarial ones — working with one another rather than against each other.

What do you/does Public Address do differently than other designers/design studios in regards to brand identities?

Our goal is to create identities that never need rebrands. Not that we don’t want them to change — we design them specifically for change. The last thing we want to create is an identity that gets in the way of that. We approach identities not as a series of limitations, but instead as catalysts for evolution. Recently, we completed a brand for a global event that won’t happen until 2028, allowing us to test this theory in a real-world (and high-stakes) project. If we guessed what a brand would look like nearly a decade away, we’d be wrong. But if the tools and design principles were designed to grow and evolve instead, we wouldn’t have to guess — the identity itself would continue to maximize relevance over consistency. Really, the question is: can you picture this brand in 10 years? 100 years? From that vantage point, it’s easier to distinguish what should stay consistent and where flexibility can be purposely built into the system. The world will certainly not stay exactly the same, so why should brand identities?

Has brand identity design changed in recent years? What do you expect for the future?

When I started working in the field more than ten years ago, a lot of focus was being put on brands literally changing — dynamic identities and the idea of using infinitely varied inputs to create infinitely varied outputs. This idea of being responsive to context signaled an enormous shift away from condensing huge ideas into single marks, but in the end, it largely meant logos with 50,000 variations — cool, but not that useful. Now we’re starting to see those roots bear fruit.

We’ve realized that dynamism goes far beyond the logo. In many ways, the idea of identity as construct has replaced the logo as the core of a brand. The public is both hyperliterate and sceptical of visual language now. They no longer need to see a logo stamped on something to identify who it’s coming from or what it’s trying to communicate. This makes formerly immutable ideas like authenticity and truth into signifiers that can be played with or deployed purposefully.

Predictions for the future always age poorly, but if the last few years have taught us anything, it’s that this rise of relevance over consistency will only accelerate. I could see brands going the way of memes — lo-fi, deep-fried — raw material that speaks in a hyperspecific language to a hyperspecific audience.

What are your thoughts on brand guidelines? How do they fit into the process?

Brand guidelines are also changing. Identities have traditionally comprised a set of rules to follow or a box to fit into. I’m sure we all miss the days of what Standards Manual is reissuing, but anything prescriptive enough to be printed in a physical book today isn’t going to last long. Guidelines used to be endpoints — today, they need to be starting points for the work that comes after the final files are handed off.

Do you have a truth/manifesto/mantra you follow when working on identities — and what is Public Addresses?

Along with many others in 2020, we lost the Italian artist Enzo Mari to coronavirus. The architect Allesandro Mendini called him “design’s conscience.” Mari had this core belief in DIY (design-it-yourself), and he spent his career trying to get workers to exercise their imaginations and their ability to think for themselves. He did this largely through antagonism and overreduction: making things harder to use or more difficult to understand. To have to learn rather than follow instructions. You see the same mentality in the Dogme 95 movement or the architecture of Arakawa and Madeline Gins. Mari didn’t quite succeed in subverting the commodity form — his artworks and objects are now going for thousands on 1stdibs — but his message is even more relevant today.

This obviously goes against the grain of what we learned in design school — graphic design’s crystal goblet, the many virtues of clarity and restraint, and so forth. But both in and outside the design world, oversimplification and neutrality now act to hide rather than reveal. The consequences of that inversion reverberate on a societal level.

I’m a firm believer that bad design is actually good. A lot of good art is bad design. Encountering it makes you zoom out. You consider your relationship with the object, how it communicates to you, and how it relates to the world in general. With design, this usually only becomes apparent when it fails. I want my work to be the visual equivalent of a push handle on a door telling you to pull it.

Public Address operates on a similarly antagonistic set of principles: no walls, no clients, no style, no end, no good. Unfortunately, we’re unable to see into the future, so our goal is to make work that grows and evolves over time, adapts to context, and most importantly, provides tools to continually create meaningful work. The guidelines we hand off at the end of the project aren’t an instruction manual. They’re a brief. This approach means working with those who don’t fit into existing categories and creating work that intentionally colors outside the lines.

For quite a while now Covid-19 has changed our everyday lives. How did it affect your workday routines and the way you handle branding projects and client relationships? How did you/Public Address adjust to this ‘new normal’?

Our team was already pretty diffuse before COVID — I’m in Los Angeles, and the rest of our team is distributed throughout Toronto and London. We were already knee-deep in daily video calls and myriad technical issues. Of course, working remotely is challenging, but staying at home 100% of the time blurs the line even further between work and life. While this now means I spend 16+ hours a day in the same room, I think we’ve all come to adapt to these circumstances quite readily — investing in a desk set up that feels good to sit at, going for walks instead of commuting to work, feeling fine about taking a break when you need one, and so on. Intentionally unstructured time has been important, as well as being open to quick, informal conversations.

What do you think are the main challenges the creative industry faces in times like this?

If anything, we’ve been busier. Small studios are uniquely positioned to take advantage of these circumstances and redefine how we work. The main casualty of the pandemic could very well be the large agency model — not only do teams need to be leaner for economic reasons but also from a strictly logistical perspective, it’s just hard to work with 50 people at once over Slack and videoconferencing. Not to mention that the layers of managers and managers of managers start to become really apparent when you can’t just spot someone from across the office.

Everyone has their own ways and means to get inspiration. What’s yours?

For lots of reasons, both political and personal, I find myself staying away from social media. Work made specifically to share on Instagram creates a cultural shorthand that is positive in lots of ways but also tends to obscure the origins of shared signifiers which offer up far more interesting narratives and rich histories that inspire in a much deeper sense. Culture trickles up, and when you’re skating on the surface of what’s on-trend, you’re only going to come up with the same ways to solve the same problems.

As a result, my research process tends to be all over the place. Looking at contemporary design work can be really useful, especially in building case studies to inform strategy and define boundaries — I do occasionally dig through the Brand New archives to find precedents — but more often than not, I find more generative inspiration in other areas: a memorable exhibition or a Comme des Garçons catalog, a 90s skate video, a forgotten photo in my camera roll, or just a poster my friend made for a DJ gig 10 years ago.

Public Address has built up a great reputation working with well-known brands and offices in Toronto, Los Angeles and London — what do you think is your key to success?

We’ve got a few on our keyring:

– We’ve been lucky to find ourselves considered for once-in-a-lifetime dream projects and have worked really hard as a team to make the most of them.

– Building partner relationships instead of client-agency ones has turned small initiatives into long-term and large-scale projects.

— The way we build brand systems has coincided and resonated with how organizations are evolving.

– Our team is incredibly talented, very hard-working, and exceedingly generous with their feedback, curiosity, and craft.

– We’re still young as a studio, so we’ve been able to keep experimenting with process — definitely something that has been helpful over the last year.

– Partners have become advocates of the studio, introducing us to great people who want exciting work.

– We’ve avoided a niche, our partners are from all over the world and span a huge variety of sectors. This makes our work interesting, but also has helped us stay busy during an unpredictable year. For personal and professional reasons, we’re thankful to Netflix, and our partners in the video game and wine industries this year.

Elliot Vredenburg is Design Director at Public Address, a brand-defining creative studio working out of LA, Toronto, and London. For the past decade, he’s worked as a multidisciplinary designer creating powerful, concept-driven work with artists, cultural institutions, and global companies, including Netflix, MGM Studios, FIFA, and Universal Music Group. He lives in Los Angeles. It’s sunny here.